Article by Tineke van den Heuvel, Partner at KennedyFitch

Open Hearts, Open Minds: Facing the full system can flip a bad situation on its head

The other day I was making my way home on my bicycle after having dropped my son off at school. As I got close to home, I noticed a little boy, 11 or 12 years old, getting off his bike in front of my house. Something seemed not right and when I approached him I saw that he was in tears, gasping for breath. I put my arm around his shoulders and said that I had asthma and knew what it feels like to struggle to breathe.

At the same time, I was also trying to gauge whether or not he needed medical assistance but I could tell that he had immediately started to relax. He shared with me that he was just starting high school and that he was late for school for the first time. It turns out he was so scared to enter that huge building and admit that he was late that he had fallen off his bike, couldn’t get back on it and had panicked. My heart went out to the boy.

As we sat on the curb, waiting for his father to pick him up, I chatted with him about different things to help calm him down. He told me that his mother had been very ill and couldn’t work. His father was working double shifts in a factory and a pizza restaurant to compensate for the loss of income, but because of the Pandemic, shifts had been limited. The boy then told me that he was the first in his family to aspire to higher education and that he was determined to have a successful career. Although wonderful to hear, I could feel his nervousness, the pressure he was putting on himself and also the pressure his environment was putting on him.

He asked me what I do for work. I explained to him how I help leaders and their teams to become more effective in their work. The exact words I used were: “To find the courage to explore what help they need to become better at what they do. Like a sort of coach, like in soccer.”. The boy looked at me and said “so you mean that bosses also need support?” with a look of relief on his face.

As you read this, you probably felt a lot of empathy for the young man and don’t put the blame for the panic attack he just experienced squarely on him. Funnily enough, as we get older, that’s often what we do. We get stuck on the doctrine of “success / failure if your own choice” and point fingers at others (he/she failed because of their own bad choices) or ourselves. I have worked with many coachees who have blamed themselves for the situations they found themselves in. Be it a burnout, a sense of loss of control, a feeling that they are not stepping into their strengths or a notion of being disconnected from their teams. When managers approach me with the ask to coach someone in their team, they also use such language: “I wish they can learn to set boundaries / find out what they need to learn to prioritize / reconnect with the team”. And they often finish with the remark “at least they see it is time for a change in their behavior so they are coachable”.

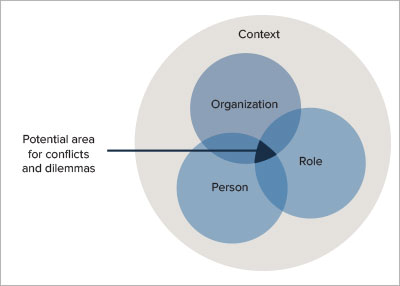

This perspective does not sit comfortably with me. It feels like putting the sole point of focus (and blame) on one person, which in my view is too limited. Not only is it too one-dimensional, it also prevents rather than enables a real change in behavior in my view. It prevents a real change in behavior because we are missing an important step in the process, namely the step in which we explore which part of what we feel belongs to us and which is actually driven by the role we are in, the organization we are part of and the context within which we operate. All of which impacts us and which we should consider, in order to take a more integrated look at what is happening within and around us.

To use the situation of the boy as an example; what makes this boy cry and other boys not? What is different in what is happening around him? In his story, the role in his family (being the first to enroll in secondary school), the impact of his home environment (his family suffering from the mother’s disease) and the context of the global pandemic, which affected his father’s work, are all aspects that had a potential impact on how the boy was feeling. Being aware of this impact and recognizing it may give him choices in how to deal with it.

I have studied, worked, and lived in the business world for more than 25 years now. And in these years, I watched it become engrained with the success is a choice doctrine through statements like “You cannot influence what happens to you, but you can decide how to deal with it,” and the good old Steven Covey “Focus on your circle of influence as all the rest is beyond your control.” I do not disagree with these statements, but over the years I have started to feel more and more uncomfortable because I feel it is too one-dimensional.

I believe it is important to acknowledge and work with a person’s wider context. This belief is founded in the Organizational Role Analysis (ORA) of the Grubb Institute of Behavioral Studies, which is in line with psychodynamic systemic thinking (Fraher, 2004). The ORA states that the role of an individual employee goes beyond the activities, responsibilities, and appropriate behaviors attached to it (Reed & Bazalgette, 2018). A person takes a role and in doing so identifies with the organization’s aim and the context it operates in and will choose the action and personal behavior to best contribute to achieving the aim. As such, the individual’s behavior is a result of constant interaction between the person, role, organization, and the organization’s context.

I believe it is important to acknowledge and work with a person’s wider context. This belief is founded in the Organizational Role Analysis (ORA) of the Grubb Institute of Behavioral Studies, which is in line with psychodynamic systemic thinking (Fraher, 2004). The ORA states that the role of an individual employee goes beyond the activities, responsibilities, and appropriate behaviors attached to it (Reed & Bazalgette, 2018). A person takes a role and in doing so identifies with the organization’s aim and the context it operates in and will choose the action and personal behavior to best contribute to achieving the aim. As such, the individual’s behavior is a result of constant interaction between the person, role, organization, and the organization’s context.

The ORA argues that it is at that intersection where there is potential for behavioral change (Reed & Bazalgette, 2018) and in my coaching practice, this is exactly what I have experienced.

Let me illustrate with an example whom I shall call Rose.

Rose had taken on a new team and was finding a challenging situation. Although Rose succeeded in securing a budget for the team and managing complex stakeholder alignment initiatives across the corporation, employee engagement scores in her new team were extremely low. In particular, the scores were low on survey questions like “I trust my manager,” “I feel my manager wants to do what is right for the team,” “I feel my manager is interested in what matters to me,” etc.

Recently, the team also expressed in a few meetings that they had completely lost their confidence in Rose as their manager. Internal discussions on the way forward did not result in tangible changes, and both Rose and her manager felt she and the team needed coaching to find out what had to change. Between the lines, I was sensing the irritation and impatience of Rose’s manager: it was time for her to get this fixed. So Rose had a lot of pressure on her shoulders. I agreed to work together with Rose and the team to discover what was going on.

Interestingly enough, I actually knew Rose from earlier in my career. At that time, when we worked together, I was impressed by the empathy Rose showed toward her team when huge organizational changes were taking place and how she had managed to keep her team engaged all the way. Clearly, when we met again years later, her situation was entirely different.

As a first step, we interviewed all team members, who expressed strong emotions in all these conversations. On the one hand, they felt frustrated with Rose; on the other hand, they felt a strong passion for the work, which was trying to find solutions to help cure a life-threatening disease.

In my conversations with Rose, I was struck by how distant she seemed toward the team members. This was very different from the empathetic woman I worked with years ago. She spoke a lot about her struggle to get all stakeholders in their corporate environment aligned, what hard work it was to secure a budget to further explore the potential solutions to cure this life-threatening disease.

What also struck me was that all team members, including Rose herself, had close experience with the disease they were researching. Either they had suffered from the disease themselves or had seen close relatives suffering from it. However, while the team members mentioned this in the 1-1 interviews, it was not something they shared with each other or with Rose. Also, Rose had not shared her close experience (her mother had passed away from the disease) with the team.

One factor they expressed as highly frustrating was that they had only limited funds to address all their promising ideas to increase the chances of finding a cure for this disease. The fact that Rose was working a 100 hours per week to try to secure as much budget from all the internal stakeholders seemed to go unnoticed by the team members. They did speak a lot about how absent she was, how distant, and at the same time how strictly she was sticking to processes and procedures within the team, in a perceived cold, distant, and micromanaging, controlling way.

Based on all the interviews, a set of interlinked hypotheses started to form:

- Could it be that the pressure of the primary task of the team, working on finding a solution for this disease, was emotionally hard to carry since in their private environment there were so many tangible examples of this disease, and so the urge felt to solve it was immense?

- Could it be that as a reaction to these hard-to carry-emotions, they felt frustrated about not being able to get all the money in the world to cure this disease with all the fantastic ideas they had?

- Could it be they felt shame and/or guilt about having to make choices about which solutions to further explore and which not, based on the available budgets?

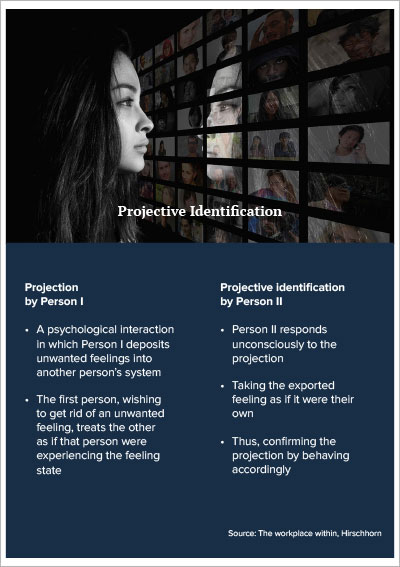

- And could it be that, to try to get rid of these feelings of guilt and/or shame, the full responsibility of making these choices they placed on the shoulders of the team manager? In other words, they decided the manager was the role to blame and shame, regardless of who was in this role?

- And could it be that Rose, unconsciously, took this in and started to behave accordingly by reacting in two ways? First, by working like crazy to secure as much budget as possible. Second, by installing very strict processes and procedures within the team to ensure she could never be blamed of making a biased, unfair, not well-documented choice? In other words, could it be that Rose was identifying with the projections being put on her? The following diagram explains what happens when we identify with what is projected on us.

In various team sessions, we started to work with these hypotheses, and they became crucial in achieving a turnaround, which they needed on the following levels:

In various team sessions, we started to work with these hypotheses, and they became crucial in achieving a turnaround, which they needed on the following levels:

- Role – For the team to express and share the strong emotions and pressures they felt about their primary task to relieve the stress and to lower the need to defend themselves against it, e.g. by projecting negative feelings like guilt or shame onto Rose.

- Organization – For the team to acknowledge that they were part of a bigger system, the organization, which meant stakeholder alignment was vital and budgets were limited, and to release the feelings of shame or guilt of not being able to work on all solutions at the same time.

- Context – For Rose to understand how and why she started to behave according to what her team projected onto her and break through this cycle.

- Person – Imperative for Rose was to explore what her valency was that led her to identify with these projections. Valency refers to the attraction of an individual for a particular patterning of emotions in a group (Morgan-Jones, 2010, p.82).

For Rose working hard had paid off in her career so far. Moreover, having worked in multiple highly regarded research environments, she had received praise for working according to validated procedures and processes. So both were always successful ingredients for her to progress in her scientific career. As such, she was vulnerable to the team’s projection on her.

Yet, doing so, she was leaving out another big part of herself by not showing her empathetic human side to this team. By showing her full self, rather than a projected, extreme version of the management role she had become, she could reconnect with the team.

This opened up to conversations in the team in which the full human aspects of each individual were disclosed more and polarizations and simplifications were decreased. Instead of arguing why Rose was a bad manager and the team members were all good, conversations took place about the personal experiences with this disease and the frustrations all felt at times when having to disappoint a patient when some research initiatives stopped.

Rose, in the end, could adjust her behavior in this specific context, in this organization in this role, to be more complete. She evolved her managerial style, which took a more integrated approach. Actively using her empathetic side to involve team members in the journey and her hard work, while she ensured the procedural side continued so that the budgets were maximized and spent as well as possible.

In my view, her management style became richer and more effective to deal with the specific demands the context, organization, and role required from her.

It takes courage to face the full system, including those things you cannot control, and then decide how to go about it. Being aware of the projections that are directed at you, through the interactions of you as a person with your role, organization, and context, is a crucial step. I often say: Emotions are also data. What you feel is an expression of what belongs to you as a person, but it happens just as much in your role, organization, and context. Ignoring this totality, or downsizing it to only focus on what you can control will lead to the false image that success and failure are both your own choice. Facing the full system, exploring it, understanding it, shedding a light on it, will eventually open up new insights, which will help you to become more effective in what you’re trying to do.

I hope this story illustrates how behavioral change is a puzzle to uncover, an integrated, multidimensional journey to undertake. It is fascinating, challenging, and incredibly interesting. It is my passion!

About the author

Tineke van den Heuvel, partner at KennedyFitch, comes from 20 years in HR transformational leadership roles in large multinational organizations and is underpinned by academic education and practical training in organizational science, business administration, Human Resources, coaching, team facilitation, and group dynamics.

Tineke van den Heuvel, partner at KennedyFitch, comes from 20 years in HR transformational leadership roles in large multinational organizations and is underpinned by academic education and practical training in organizational science, business administration, Human Resources, coaching, team facilitation, and group dynamics.

She has a proven track record in large-scale global transformational change, with a special focus on all leadership-related and organizational culture challenges, touching head and heart in organizational -, team – and individual processes.

Email: tineke.vandenheuvel@kennedyfitch.com

Sources

- Fraher, A. L. (2004). Systems psychodynamics: The formative years of an interdisciplinary field at the Tavistock Institute. History of Psychology, 7(1), 65-84. https://doi.org/10.1037/1093-4510.7.1.65

- Klerk, J. J. (2021). Combining ethics and compliance: A systems psychodynamic inquiry into praxis and outcomes. Business Ethics, the Environment & Responsibility, 30(3), 432-446. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12336

- Reed, B., & Bazalgette, J. (2018). Organizational role analysis at the Grubb Institute of Behavioural Studies: Origins and development. In Reed, B., & Balgazette, J., Coaching in Depth (pp. 43-62). Routledge

- Yilmaz, D., & Kılıçoğlu, G. (2013). Resistance to change and ways of reducing resistance in educational organizations. European Journal of Research on Education, 1(1), 14-21. Retrieved from this link

- Armstrong, D. (2010). Meaning found and meaning lost: On the boundaries of a psychoanalytic study of organisations. Organisational & Social Dynamics 10 (1), p.99-117.

- Hirschhorn, L. (1998) The workplace within: Psychodynamics of organizational life. Cambridge/London: MIT Press.

- Obholzer, A., Zagier Roberts, V. (eds) (1994) The Unconscious at Work. Individual and organizational stress in the human services. London: Routledge.

- Chapter 1: Halton, W., Some unconscious aspects of organizational life. Contributions from psychoanalysis, pp. 11-18.

- Obholzer, A. (1994). Chapter 4: Authority, power and leadership. Contributions from group relations training. Editor, Obholzer, A. & Zagier Roberts, V. (Eds.), The unconscious at work. Individual and organizational stress in the human services. (pp. 39-47). London, UK: Routledge. ISBN 0415102065

- Remmerswaal, J. (1996). Psychoanalyse en groepsdynamica Editor, J.M.L. Remmerswaal, Editor L. Dekeyser (Eds.), Werken, leren en leven met groepen. (p. A2200-1-A2200-45). Houten: Bohn Stafleu Van Loghum.

- Remmerswaal, J. (2015). Begeleiden van Groepen: Groepsdynamica in de Praktijk. Houten: Bohn Stafleu Van Loghum.

- Vansina-Cobbaert, M.J., L. Vansina (1996) W. Bion Inzichten en bijdragen aan de groepsdynamica, Editor, J.L.M. Remmerswaal, Editor L. Dekeyser (Eds.), Werken, leren en leven met groepen (p. A2050-1-A2050-21). Houten: Bohn Stafleu Van Loghum.